When I was in college, if I needed to gather information for a report, essay, or class project, the process was long and, honestly, a bit grueling. I had to walk to the campus library, dig through tall wooden card catalogs — those five-foot cabinets filled with little drawers. Each drawer held hundreds of paper cards, about the size of a 3×5 index card, and each card gave me just the basics: title, author, date, and where to find the book. After scribbling down a list of promising sources on a sheet of notebook paper (in cursive because it is faster than printing), I’d venture into the stacks, gather my haul, and sit at a long table to begin sorting through it all.

There were no laptops. No Wi-Fi. The only computers were in a separate building, and you had to type out your paper on one of those clunky machines after your research was done, and that was only if you got a seat.

Fast forward to today, and with just a few clicks, I can access an ocean of information that is organized, searchable, and cross-referenced, thanks to something the tech world calls “Artificial Intelligence.” But here’s the rub: that name, “Artificial Intelligence,” is completely misleading.

Why Misleading, You Ask?

Let’s go back to where it all began. The term “Artificial Intelligence” was coined in 1956 by a group of ambitious researchers by the names of John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Claude Shannon, and Nathaniel Rochester during a brainstorming session at Dartmouth. They weren’t trying to be precise; they were trying to be bold. And to be honest, the name sounded good. It captured imaginations. But from day one, it promised far more than the technology could actually deliver.

They weren’t saying, “Hey, we’ve built a mind!” They were saying, “We think it might be possible to simulate learning someday.”

What happened instead was a decades-long journey of building very specific, very task-oriented software. This stuff that could play checkers or help chemists identify molecules, but not think, feel, or understand. These were rule-based systems, later called expert systems, and all they really did was follow instructions. Like an Excel spreadsheet on steroids.

Later, in the ’90s and beyond, we got machine learning. These systems could sift through massive data sets and find patterns. Google Translate, for example, doesn’t “understand” language. It’s just gotten good at predicting what words are likely to come next based on billions of examples.

More recently, things like ChatGPT have entered the picture. And while it can write whole essays or poems, it doesn’t know what it’s saying. It’s just really good at generating language that sounds like it makes sense.

It’s all what computer scientists call narrow AI. These are tools built for specific tasks. These are not minds. There are no brains in a box, no digital people.

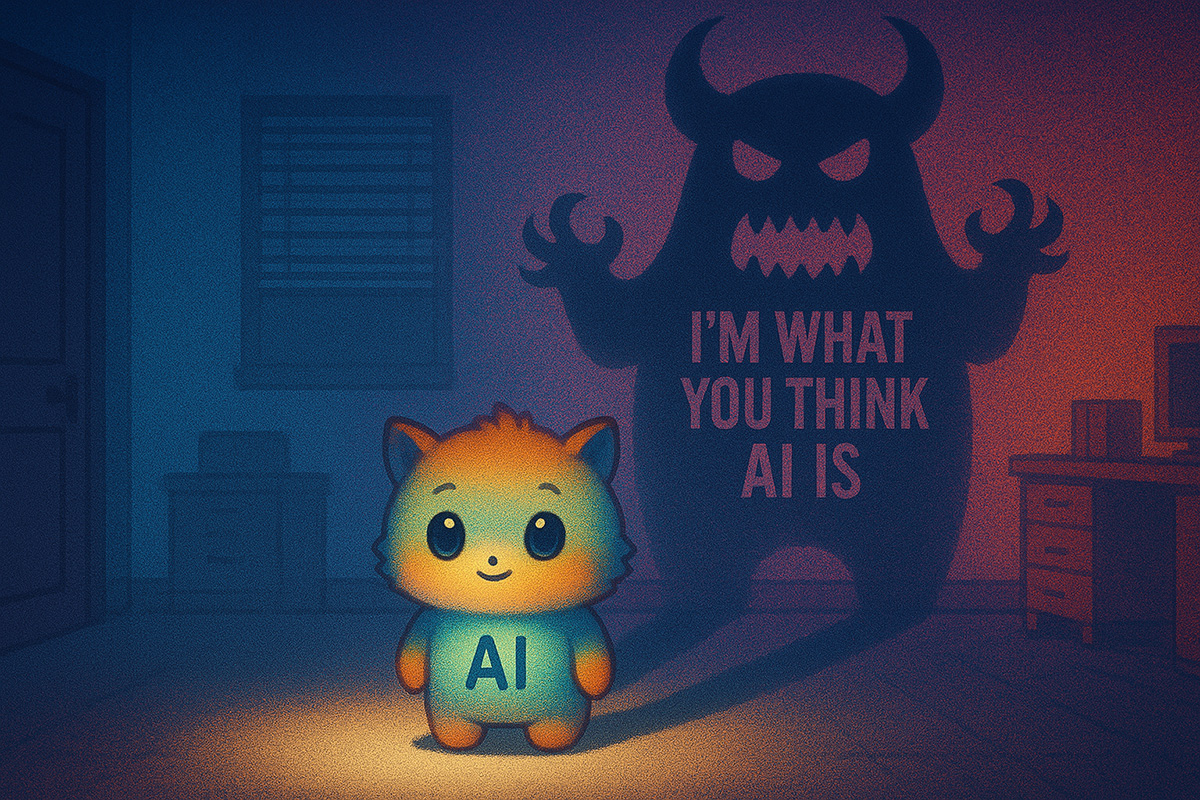

Here’s where the confusion really takes hold: the name “Artificial Intelligence” makes us think of robots with personalities, killer computers, or machines with opinions. Movies like The Terminator or 2001: A Space Odyssey have trained us to expect sentience. But the truth is far less exciting—and far more useful.

- There is no thinking.

- There is no self-awareness.

- There is no emotion.

- There is no moral judgment.

There is only programming.

It’s like this: If a light is red, stop. If it’s green, go. If it’s yellow and the light stays yellow for three seconds, then if it’s been yellow less than 1.5 seconds, speed up. Otherwise, slow down and prepare to stop. That’s not a decision. That’s a flow chart. That’s a set of instructions. That’s what computers do.

- Does AI lie? Only if it’s programmed to.

- Does it try to hide or escape? If someone codes it that way.

- Does it want to take over the world? Absolutely not. It doesn’t want anything.

Even in cases where the software is designed to “learn,” what it’s really doing is updating mathematical models based on data. It doesn’t gain wisdom or experience. It doesn’t form opinions. It doesn’t reflect. There’s no little ghost inside the machine.

To be fair, some of the confusion isn’t just from Hollywood. It comes from the language we use. We say these systems “learn” or “hallucinate” (when they generate wrong answers), but that’s just a convenient metaphor. They don’t hallucinate the way humans do. They don’t learn like children. It’s just math, statistics, and lots of data.

So What Should We Call It?

Some experts suggest names like machine learning, pattern recognition systems, or data-driven algorithms. They may not sound as exciting, but they’re much more accurate. They describe what’s actually happening without all the scary movie baggage.

And here’s the real shame: all this hype and fear has kept a lot of people from exploring just how helpful these tools can be. AI, or whatever we end up calling it, can save time on tedious tasks, help us make sense of complex information, and automate things we once had to slog through by hand.

It’s not a monster. It’s a tool.

And like any tool, what matters most is how we humans choose to use it.

But here’s a final thought — if “AI” frightens you, then you really shouldn’t be using a smartphone. You probably shouldn’t be on Facebook, or YouTube, or even letting Netflix recommend your next show. These platforms run on the same kinds of data-driven algorithms, and they are programmed to influence your behavior in subtle, persistent, and sometimes manipulative ways. And unlike ChatGPT, they don’t just answer your questions, they shape what you see, how you feel, and sometimes even what you believe.

So if you decide to be brave and try out these new tools (just like people once had to get used to pencils, the printing press, and typewriters), remember this: you can always unplug it. Turn it off. Walk away. Go outside. Let the dog sniff a tree. AI won’t chase you. It doesn’t care.

Because, after all, it’s not intelligent.

It’s just code.

Note: Computer programming is written in a special language and can be very complex. If you are interested in trying out a simplified version, check out Scratch at https://scratch.mit.edu/. It is aimed at children but is fun and very informative for everyone.